|

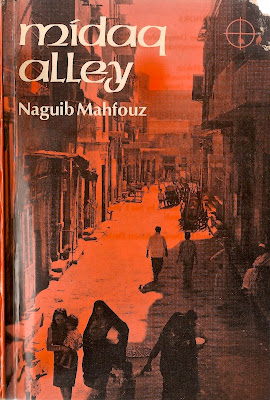

| My old Heinemann edition of Midaq Alley. |

The book that first truly announced to Egypt the literary arrival of Naguib Mahfouz was Midaq Alley, published in Cairo in 1947. I read it in the old Heineman Arab Authors paperback edition in 1979, and as soon as I could I went looking for Midaq Alley itself, discovering it buried away on the edge of Khan el Khalili, off Sharia el-Sanadqiya near the corner with the once fabulous Sharia al-Muizz, the high street of Fatimid Cairo.

In his novel Mahfouz describes Midaq Alley like this.

Many things combine to show that Midaq Alley is one of the gems of times gone by and that it once shone forth like a flashing star in the history of Cairo. Which Cairo do I mean? That of the Fatimids, the Mamelukes or the Sultans? Only God and the archaeologists know the answer to that, but in any case, the alley is certainly an ancient relic and a precious one. ... Although Midaq Alley lives in almost complete isolation from all surrounding activity it clamours with a distinctive and personal life of its own. Fundamentally and basically, its roots connect with life as a whole and yet, at the same time, it retains a number of the secrets of a world now past.At the death of Mahfouz in 2006 I wrote an article in The Los Angeles Times describing the significance of Midaq Alley.

After World War II, Mahfouz rejected the romanticizing nationalism then in vogue and abandoned writing novels about what he called "the grand avenues and boulevards" of history. Instead, he turned his attention to what we cherish most about his great works: life in the small alleyways, homes, cafés and mosques of Cairo's old quarter. It was a fateful decision: Writing a literature of everyday city life in the vernacular was a decisive step toward an Arab recognition of modernity and its challenges.To read the complete article in The Los Angeles Times, click here.

I read other books by Mahfouz published in English by Heinemann in London and by The American University in Cairo Press in Egypt. But very few other people did. Heinemann was selling not more than three hundred copies of all his works a year and regarded the enterprise as such a waste of their resources that they gladly surrendered the British publishing rights in early 1988 - a decision they very soon regretted when a few months later Mahfouz won the Nobel Prize for Literature, making him instantly marketable round the world.

In 1994 Mahfouz was attacked by fanatical Islamists and stabbed in the neck; he survived but almost entirely lost the use of his right arm and thereafter had to dictate almost everything he wrote. His troubles with Islamists began after 1959 when he published The Children of the Gebelawi, a religious and social allegory in which God, Moses, Jesus and Mohammed appear; the novel was quickly banned and Mahfouz was accused of blasphemy.

| |

| My copy of The Dreams signed 27 April 2005 by Mahfouz showing the effect of the murder attempt. |

Earlier Mahfouz had found himself at odds with Nasser's regime, not an attitude shared at the time by the generality of Egyptian writers. He expressed his criticisms of the regime in Miramar, published just before the 1967 war and set significantly in Alexandria whose cosmopolitan and outward-looking society was in its death throes.

By then it was clear to Mahfouz that apart from specific political and economic mistakes made by Nasser's regime, the real damage lay in its moral failure, where rhetoric and reality bore no relation to one another, where terms like 'social equality', 'freedom of the individual' and 'the rule of law' had no meaning, and where cynicism, nihilism, self-interest and self-contempt were the result.

Zohra, the peasant girl working at the Miramar pension, earns the admiration or resentment of the men around her by her desire to learn and emancipate herself - under various names this eternally striving female figure appears in Mahfouz's novels where she represents Egypt.

At the end of the book, as Zohra leaves the pension for what she hopes will be a better job, an old man long resident at the Miramar tells her, as Mahfouz might have said of Egypt in these recent years: 'Remember that you haven't wasted your time here. If you've come to know what is not good for you, you may also think of it all as having been a sort of magical way of finding out what is truly good for you'.

Politics aside, Miramar marked a literary turning point for Mahfouz; his one Alexandrian novel was conciously influenced by Lawrence Durrell's Alexandria Quartet, and Mahfouz now began writing in a freer style with multiple narrative voices and interior monologues.

|

| The Dreams published by The AUC Press. |

The last of these stories is Dream 104.

I saw myself in Abbasiya wandering in the vastness of my memories, recalling in particular the late Lady Eye. So I contacted her by telephone, inviting her to meet me by the fountain, and there I welcomed her with a passionate heart. I suggested that we spend the evening together in Fishawi Café, as in our happiest days. But when we reached the familiar place, the deceased blind bookseller came over to us and greeted us warmly - though he scolded the dearly departed Eye for her long absence.

She told him what had kept her away was Death. But he rejected that excuse - for Death, he said, can never come between lovers.